Grazing in Existing Grasslands

Grazing can be used to maintain disturbance-adapted sandplain grasslands by manipulating ecological succession. The principal goals of management with grazing are to reduce woody vegetation cover, create conditions that maintain plant and animal species that rely on grassland habitat, alter soil conditions, and reduce fuels and fire risk.

Figure 1. Sheep grazing shrubs at Squam Farm, Nantucket. Credit: Gregory Stroud.

Grazing in sandplain grasslands typically aims to promote a diverse assemblage of target grassland species with a high proportion of warm-season grasses and native forbs, a low proportion of cool season grasses and non-native invasive species, while reducing the growth of woody shrubs (Fig. 1). Grazing is used in grassland management to affect vegetation composition and structure by top-killing vegetation. Grazing can also maintain low fuel loads that reduce fire hazards by consumption and expose mineral soils and maintain microclimates by compaction that fosters germination and regeneration of disturbance-dependent grassland species.

The consequences of grazing on sandplain grassland vegetation largely depend on pre-treatment vegetation and grazing variables such as type of animal, seasonality, and grazing intensity, which can influence the effectiveness of grazing, as well as palatability of pre-treatment species. Grazing is equipment-intensive, complicated, costly and requires the availability of staff that are knowledgeable about grazing, ecology and overall management goals. These factors influence the effectiveness of grazing for maintaining sandplain grasslands. Management experience with grazing and carefully planned experimental grazing treatments during the last several decades provide information on grazing effects in sandplain grasslands. Management of sandplain grasslands using grazing can be complex and is influenced by conditions that change on a short-term basis, even where the effects of grazing are tested in planned experiments.

In this document, we evaluate the effects of grazing in sandplain grasslands compiled from published and unpublished studies and information obtained from interviews with land managers. We focused on the following main questions relevant for sandplain grassland management:

1) Does grazing limit woody growth?

2) Does grazing maintain or increase grassland associated plant and animal species diversity?

3) Under which conditions is grazing more or less effective at reducing woody species cover?

4) How can the effectiveness of grazing be improved as a management tool to maintain sandplain grasslands?

We focus on interpreting the main patterns that emerge from examining multiple experiences across multiple sites, with the understanding that responses in any one grazing treatment under particular conditions may differ.

These studies represent only a portion of possible treatments and variables that could be tested. It is challenging to design and execute well-controlled studies to determine the impacts of management techniques on sandplain grassland when considering the combinations of individualistic species responses, treatments, short and long-term effects, and the number of replicates needed for sound investigations (Dunwiddie 1990).

Methods

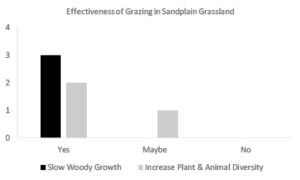

We reviewed 75 sources that described or documented results of management actions in sandplain grassland. Of these, eight sources contained information on grazing and two detailed a specific management experiments or case studies (Fig. 2). In addition, we interviewed 3 professionals in the region about their experiences with grazing in sandplain grasslands. Literature sources that tested active management treatments were classified by whether they: (1) reduced regrowth of woody vegetation and (2) increased biodiversity of plants or animals, or both (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Number of sources that found prescribed fire in sandplain grassland reduced woody shrub and tree regrowth.

We used this review and interviews to summarize the state of current management understanding grazing combinations in sandplain grasslands and the effects of grazing on: (1) soils and fuels, (2) vegetation composition, (3) vegetation structure, and (4) fauna in relation to important grazing variables. We then suggest ways that the use of grazing could be improved to decrease woody cover, increase graminoid cover, and maintain and promote biodiversity in sandplain grassland.

Results

Overall, the majority of sources found that grazing reduced the regrowth of woody vegetation and increased biodiversity in some manner (Fig. 2). However, no study found that grazing alone was completely effective over the long term in reducing woody regrowth or increasing biodiversity. Rather, our review found that pairing grazing with other management practices will be needed to control woody regrowth and maintain sandplain grassland biodiversity over the long term.

Figure 2. Cattle enclosure experiment on Naushon Island testing stocking rates of cattle. Credit: Lena Champlin.

Based on ten years of targeted sheep grazing experience at Squam Farm on Nantucket, the Nantucket Conservation Foundation concluded that managing live animals in a humane and sustainable manner is equipment-intensive, complicated, costly and requires the constant availability of staff. Maintaining a year-round core breeding flock is an integral part of a targeted grazing program. During the winter, it is necessary to provide high-quality hay and grain supplement to optimize breeding and nutrition, maintain sheep in permanent fencing capable of withstanding snow, and have the capacity to provide water during below-freezing conditions. Hay purchased for livestock grazing typically contains a mixture of native and non-native (often invasive) species seed that can add undesirable consequences to sandplain grassland. Annual vaccinations for rabies, intestinal parasites, and others are costly but necessary to maintain flock health. The availability of highly trained staff with the interdisciplinary skills necessary to oversee both sheep flock health and land management goals is one of the most important elements of a targeted grazing program and the highest financial cost.

Expanding grazing on existing new, local, commercial, or non-profit farms has been suggested as a way to increase regional food production (Donahue et al. 2014). While most of this grazing would presumably occur on managed agricultural grasslands that do not have the typical flora of sandplain grasslands, there could be potential to incorporate some animal use on existing sandplain grasslands, or to use grazing animals in efforts to either expand sandplain grasslands from woodlands or to transition agricultural grasslands to sandplain grasslands. Partnership farms would reduce the responsibility of land management organizations for animal husbandry, and potentially costs. However, any use of animals on existing high-quality sandplain grasslands would require further study to examine potential effects on target species and require carefully-constructed management plans to ensure that conservation management rather than food production remains the primary objective on these lands.

The effects of grazing on vegetation composition in sandplain grasslands and effects of grazing variables have been studied in field management experiments. The types of animals, seasonality, and grazing intensity are the most important variables that control the outcome of grazing management. Goats are recommended to control woody vegetation, sheep for a mix of woody growth and forbs, and cattle if there is a high proportion of graminoids. Evidence suggests that grazing could have long-term positive effects to maintain sandplain grasslands, but a release period seems to be important over some interval. Logistical and practical constraints are high for this practice. Ultimately, there has been little work on the effects of grazing in sandplain grasslands. Future research should incorporate different animal, seasonality and grazing intensity treatments into experiments and examine grazing in combination with other management practices. A major challenge for the use of grazing for long-term management of sandplain grasslands is the ability to apply it effectively given the complexity of logistical constraints.

This review identified several major ways to improve understanding and potential benefits of the use of grazing for sandplain grassland management.

(1) Test combinations of grazing with other management techniques. They should be designed and monitored as field experiments. Treatments should be designed in sites with well-understood land-use histories to factor in pre-existing conditions;

(2) Improve understanding of how infrequent or rare plants respond to different grazing treatments. These rarer plants are some of the major targets for sandplain grassland management and often have life histories that differ from closely-related but more common species. There is currently almost no information on how these species respond to grazing and the effects of seasonality, grazing intensity or type of animal.

(3) More work is needed to determine how grazing affects population dynamics of fauna in sandplain grassland. These effects may be particularly important for less common and conservation target species that have small and dispersed populations. It is also important for higher-profile species such as birds and for more common species such as some invertebrates.

References

Bullock, J.M., Clear Hill, B., Dale, M.P., & Silvertown, J. 1994. An experimental study of the effects of sheep grazing on vegetation change in a species-poor grassland and the role of seedling recruitment into gaps. Journal of Applied Ecology 31: 493–507.

Bullock, J.M., Silvertown, J., & Sutton, M. 1995. Gap colonization as a source of grassland community change: Effects of gap size and grazing on the rate and mode of colonization by different species. Oikos 72: 273–282.

Burrit, E., & Frost, R. 2006. Chapter 2: Animal behavior principles and practices. In Launchbaugh, K., Walker, J.W., & Daines, R.J. (eds.), Targeted grazing: A natural approach to vegetation management and landscape enhancement, p. 10. American Sheep Industry Association, Centennial, CO.

Donahue, B., Burke, J., Anderson, M., Beal, A., Kell, T., Lapping, M., Rammer, H., Libby, R. & Berlin, L. 2014. A New England Food Vision. Food Solutions New England, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH. 45 pp.

Dunwiddie, P.M. 1990. Priorities and progress in management of sandplain grasslands and coastal heathlands in Massachusetts. Nantucket, MA. Report, unpublished.

Dunwiddie, P.W. 1997. Long-term effects of sheep grazing on coastal sandplain vegetation. Natural Areas Journal 17: 261–264.

Dunwiddie, P.W. 1986. Sheep grazing on Nantucket: Preliminary analysis of 1986 data. Nantucket, MA. Report, unpublished.

Forbes, D.J. 2011. The effects of livestock grazing and mowing on succession in a coastal grassland.

Hendrickson, J., & Olson, B. 2006. Chapter 4: Understanding plant response to grazing. In Launchbaugh, K., Walker, J.W., & Daines, R.J. (eds.), Targeted grazing: A natural approach to vegetation management and landscape enhancement, pp. 32–39. American Sheep Industry Association, Centennial, CO.

Karberg, J.M., & Beattie, K.C. 2009. Effectiveness of sheep grazing as a management tool on Nantucket Island, MA. Internal report, unpublished to Nantucket Conservation Foundation, Nantucket, MA.

Kott, R.T., Faller, T., Knight, J., Nudell, D., & Roederm, B. 2006. Chapter 3: Animal husbandry of sheep and goats for vegetative management. In Launchbaugh, J.W., Walker, J.W., & Daines, R.J. (eds.), Targeted grazing: A natural approach to vegetation management and landscape enhancement, pp. 22–31. American Sheep Industry Association, Centennial, CO.

Launchbaugh, K., & Walker, J.W. 2006. Chapter 1: Targeted grazing – a new paradigm for livestock management. In Launchbaugh, K., Walker, J.W., & Daines, R.J. (eds.), Targeted grazing: A natural approach to vegetation management and landscape enhancement, pp. 2–9. American Sheep Industry Association, Centennial, CO.

Makkar, H.P.S. 2003. Effects and fate of tannins in ruminant animals, adaptation to tannins, and strategies to overcome detrimental effects of feeding tannin-rich feeds. Small Ruminant Research 49: 241–256.

Makkar, H.P.S., Dawra, R.K., & Singh, B. 1991. Tannin levels in leaves of some oak species at different stages of maturity. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 54: 513–519.

Patterson III, W.A., Clarke, G.L., Haggerty, S.A., Sievert, P.R., & Kelty, M.J. 2005. Wildland fuel management options for the central plains of Martha’s Vineyard: Impacts on fuel loads, fire behavior and rare plant and insect species. Amherst, MA. Unpublished report to Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, Westborough, MA.

Silvertown, J., & Smith, B. 1988. Gaps in the canopy: The missing dimension in vegetation dynamics. Vegetatio 77: 57–60.

Zaremba, R.E. 2003. Linum sulcatum Riddell (Grooved flax) conservation and research plan for New England Wildflower Society. Framingham, MA.

Other Sources

Dunwiddie, Peter. Interviewed by Lena Champlin. November 17, 2016

Hopping, Russ. Interview by Lena Champlin. January 10, 2017

Neill, Chris. Interview by Lena Champlin. November 2, 2016